Chapter 3: The Clipped Wings of Man

- Owner: crossfire (View all images and albums)

- Uploaded: Aug 30 2024 11:38 AM

- Views: 656

- Album Alpha Timeline

Eastern Air Lines had long been the ailing giant of the American aviation industry, staggering from one financial crisis to the next and barely scraping by with modest profits. Even before deregulation, Eastern was notorious for its inconsistent service and aging fleet, a stark contrast to its more agile and customer-focused rivals. When deregulation finally hit, it proved nothing short of catastrophic for Eastern.

In a desperate bid to stabilize its shaky position, Eastern saw an opportunity to grow—or at least eliminate some competition—by acquiring National Airlines. But this plan was swiftly thwarted by the tenacious Frank Lorenzo, who outmaneuvered Eastern in the race to secure the deal. The federal government stepped in as well, ultimately blocking any potential merger between the two airlines, a decision that Frank Borman, Eastern’s CEO, bitterly accused of being the result of collusion between the government and Lorenzo. Looking back, though, it’s likely that an Eastern-National merger would have only hastened Eastern’s downfall. Combining two airlines would have simply compounded the debt and operational issues, dragging the airline further into the financial quagmire.

As 1980 dawned, Eastern faced fierce competition on its home turf in Miami from three main rivals: Air Florida, Pan Am, and National. ir Florida, a nimble low-cost carrier, had taken advantage of deregulation to carve out a niche with aggressive pricing and a lean operational model. But as the years passed, the airline seemed to self-destruct. The tragic crash of Flight 90 and the brutal airfare wars that followed dealt fatal blows to Air Florida, leading to its collapse in January 1983 and its eventual acquisition by the hungry Midway Airlines in 1985. Pan Am, meanwhile, focused its Miami operations on routes to Latin America, a market that Eastern had yet to effectively penetrate, choosing instead to bolster its domestic position. TWA had not provided Pan Am with a strong feeder network to Miami, unlike JFK or LAX, leaving it less of a direct threat to Eastern’s domestic network, but it still siphoned off valuable traffic and connections.

However, it was National Airlines that became the most persistent thorn in Eastern’s side. Under Lorenzo’s leadership, National aggressively slashed overheads and reduced fares, drawing passengers away from the more expensive and stuffier Eastern. National steadily gained market share in Miami, capitalizing on its energetic and lower-cost offerings.This loss of market share in Miami forced Eastern to re-evaluate its strategy, but every move seemed to come too late or face insurmountable obstacles.

Eastern attempted to strengthen its position with its other hubs, but with limited success. In Atlanta, Eastern’s second-largest hub, Delta Air Lines was a formidable opponent. Delta’s conservative business practices and strong customer service made it the preferred choice for many travelers, and Eastern’s attempts to reclaim ground in Atlanta were largely unsuccessful.

By the first quarter of 1982, Eastern’s financial situation had grown increasingly dire, with the airline recording a $75 million loss—a significant drop from the $10 million loss in the previous quarter. The situation worsened when National Airlines announced on April 25th that it had acquired Braniff’s Latin American routes for $11 million. This move left Eastern at a severe disadvantage in the Miami market, as both Pan Am and National now had direct gateways to South America, capturing a larger share of the lucrative travel market to the region and further eroding Eastern’s position.

In a desperate attempt to cut costs, Eastern entered into tense negotiations with its unions, proposing a 30% across-the-board salary cut. The unions, already wary of the airline’s unstable management, rejected the proposal outright and threatened to strike. Knowing a strike could be a death blow, Eastern backed down and instead resorted to cutting services. This decision only alienated its loyal customer base further, as service cuts led to deteriorating passenger experiences without achieving the necessary fare reductions to compete with National and the emerging low-cost carriers.

As these struggles unfolded, Eastern’s debt continued to skyrocket, surpassing $1 billion. The airline was now paying crippling amounts of interest daily, with no clear path to solvency. By March 1983, Eastern was on the brink of collapse, announcing that it was just one month away from defaulting on its loans and pleading with creditors for leniency. However, these creditors refused to grant Eastern any more leeway, and investors were hesitant to pour money into an airline teetering on the edge of bankruptcy.

On April 20th, 1983, Eastern Air Lines officially filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The news rocked the airline industry and made front-page headlines across the country. Frank Borman, attempting to calm the nerves of passengers and investors, declared, “This is a minor setback. We will exit bankruptcy protection stronger than ever.” Borman also promised that the filing would not affect Eastern’s operations. For the moment, that was true, as Eastern continued to fly while the courts approved its plan to shrink into a leaner, more profitable airline.

Eastern’s main strategy was to eliminate the Atlanta hub and sell the assets connected to it. The airline also planned to restructure its route map, eliminating spokes and creating a strict feeder system from its two remaining hubs in Miami and New York. Most of the assets in Atlanta—including aircraft, crews, and gate slots—were sold to Delta, which now enjoyed a near-overwhelming presence at the airport. At other airports, gate slots were sold to airlines like Piedmont in Charlotte and USAir in Philadelphia. The latter deal helped USAir build up a hub in Philadelphia later in the decade. One of Eastern’s more valuable assets, the Shuttle, was sold to Texas Air for $215 million.

Despite these sell-offs, they failed to make a significant dent in Eastern’s towering debt. Passengers, fearful of another Braniff-style collapse, avoided flying with Eastern after the bankruptcy filing, and Borman’s promises did little to soothe their concerns. Throughout the summer of 1983, the number of passengers flying Eastern plummeted by 40%. The restructuring of the airline’s route systems led to operational issues and widespread complaints, and Eastern was lambasted by the media for its declining on-time performance and increasingly surly staff.

When Borman received the financial records for that summer in mid-September, he was appalled. The airline’s losses were a staggering $95 million for the third quarter, a sharp decline from the $50 million loss in the second quarter. In its efforts to trim its network and focus on its hub-and-spoke system, Eastern had inadvertently put itself in direct competition with other airlines out of Miami and New York. The writing was on the wall: management knew it was time to bring Eastern’s long struggle to an end.

On September 28th, 1983, Eastern suddenly shut down, leaving thousands of employees out of work and countless passengers stranded. The abrupt closure sent shockwaves through the aviation industry, marking the end of an era for one of America’s oldest and once most celebrated airlines. For many employees, this event was a somber moment, with hundreds gathering at the airline's headquarters in Miami for a tearful farewell, their futures uncertain. Others felt betrayed, and emotions ran high. The day after the shutdown, a distraught employee rammed his truck into the forward landing gear of a parked Eastern 727 at Miami. The impact caused minor damage to the aircraft, but the truck’s windshield and canopy were shattered, killing the employee from blunt force trauma.

Borman, now bearing the full weight of his decisions, issued a final statement to the press on September 29th, acknowledging the airline’s failure and expressing deep regret for the impact on workers and passengers alike. In a final decision by management, Borman announced that Eastern’s bankruptcy filing would be converted to Chapter 7, with auctions of the airline’s assets to begin immediately, ushering in a dramatic new chapter in the Eastern saga.

In the aftermath of Eastern’s collapse, Pan Am and National swooped in like vultures, eager to capitalize on the airline’s demise. To prevent a prolonged crisis, the government temporarily lifted antitrust reviews on Pan Am and National, encouraging them to quickly fill the void left by Eastern. The two airlines went on a buying spree at Miami, acquiring 85% of Eastern’s former gate slots and a large portion of its fleet. National snapped up DC-9s and A300s, bolstering its domestic fleet and adding widebody aircraft to support its Latin American services. Airbus, eager to expand its presence in the American market, offered maintenance and support at a discounted price, which Lorenzo readily accepted. With the addition of the A300s, National freed up its DC-10s for new European routes. Pan Am, on the other hand, took up 727s and L-1011s. Other airlines snapped up the remaining assets, with Northwest Orient buying all of Eastern’s slots at Washington National and Eastern’s 757 order and aircraft, since the 757 had been on the Northwest Orient’s radar for some time.

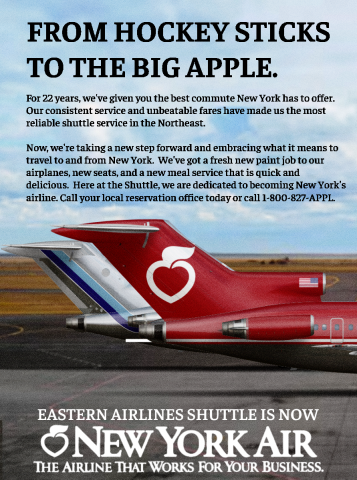

Meanwhile, Texas Air Corporation completely transformed the Eastern Airlines Shuttle when it fell into their hands, rebranding it as New York Air. A massive ad campaign followed, and Eastern Shuttle planes were repainted in a crimson red scheme with an apple logo. In-flight dining was changed to a meal bag named “The Flying Nosh.” Predictably, Lorenzo slashed salaries and overheads to suit the new low-cost business model. Over the next few years, New York Air expanded south, adding new routes to Florida and North Carolina.

The Eastern name flew once again in 1984 with a new airline. Attorneys Michael Hollis and Daniel Kolber were planning to launch an Atlanta-based airline when they purchased the rights to Eastern Air Lines, renaming their proposed airline from Air Atlanta to Eastern Airlines Inc. The new, smaller Eastern sported an updated brand and a high level of service for more competitive prices. The all-727 fleet flew independent routes from Atlanta, as well as routes under the Pan Am Express brand. Due to unfavorable market conditions and rising costs, the second Eastern shut down by 1987.

As the dust settled from Eastern’s collapse, the American aviation landscape was irrevocably altered. Eastern’s demise served as a stark lesson for the industry: even the biggest players must adapt and react, or they will inevitably fall.

Sign In

Sign In Create Account

Create Account

i have hope for more lore for this, i also appreciate this aswell, keep up the good work!