history of the entire Royal Omani, i guess

- Owner: ThePessimist (View all images and albums)

- Uploaded: May 27 2022 06:44 PM

- Views: 1,393

- Album The Pessimist One Offs

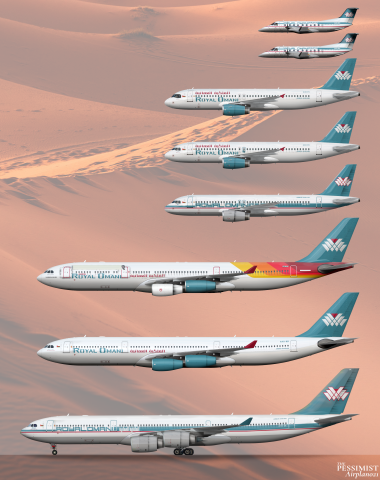

Royal Omani is the flag carrier of Oman. It was created by the Sultan in 1964 with the ostensible goal of allowing Omanis to make connections to the wider world. Early operations featured a selection of DC-3s up to DC-6s. In 1967, the airline acquired twin DC-8s from Simmons which could easily make nonstop flights from Muscat to European capitals or even further afield. This relegated the DC-3s to hopper services between Muscat and numerous smaller airports across Oman, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the Trucial States. This spending spree previewed a pattern which would pervade Royal Omani for much of its history. Long periods of stagnation punctuated by infrequent cash injections.

The next cash injection occurred when Oman’s new Sultan, looking to improve his image, wished to inaugurate nonstop flights from Muscat to exotic, prestigious locales like New York City. This necessitated the purchase of used long-haul widebody aircraft. In 1982, Royal Omani acquired a used 747SP from African. The next year, an advanced Lockheed L1011 Tristar joined the fleet courtesy of Dragonair.

In 1987, the Sultan embarked on a series of trips to countries with which Oman had few or no previous international relations. One such nation was Brazil. The Sultan enjoyed the weather as well as the culture of Brazil during his visit. Brazil’s president, hoping to offload some foreign debt, gave the Sultan the hard sell on his nation’s mechanical crown jewel. The EMB-120 Brasilia was a turboprop built to handle rough, extreme conditions. Thus, it made for a perfect replacement to Royal Omani’s fleet of frankly decrepit DC-3s, which, due to their advanced age, now spent more time as expensive paperweights than modes of transportation. The Sultan bit on the offer and by 1989 Royal Omani added a pair of the new type to their fleet. They would be the first aircraft acquired by the carrier brand new. These would also be the first aircraft to feature what the Sultan would describe as “a new livery for a new era in Omani transportation.” The livery featured modern design trends including a geometrically stylized iteration of the airline’s traditional crown logo and brightened colour palette. The aircraft were registered A4O-BA and A4O-BB respectively and were named after some of the smaller Omani cities they served.

Revamped smaller regional services commenced with an emphasis on using the Brasilias to build more frequent service to airstrips across Oman. However, the Sultan was not done spending quite yet. The DC-8s used on Royal Omani’s mid-length hops like the route to Dubai were rather long in the tooth and subject to ridicule, particularly given the increasingly glamorous images of national carriers hailing from other Arab kingdoms. The Sultan was not persuaded by supporters of an all new narrowbody jet fleet. Instead, Royal Omani sought to acquire used aircraft that would appear more modern. In 1993, airline management struck gold. The A320-200 was the modern flagship of many airline’s operations. New A320-200s were expensive and the used market for the type featured high demand and low supply. However, the A320-100 – the less successful original variant of the type – was not nearly as much of a hot commodity. Airlines operating the A320-100 were interested in replacing these craft with A320-200s which were better in every way. But Royal Omani didn’t need the extra range or fuel efficiency. A320-100s were still relatively modern. The carrier struck a deal to acquire two early A320-100s operated by British Atlantic in late 1993. One of the DC-8s remained in service after this date to cover certain charter and peak flights like those to Mecca, but the other was unceremoniously dumped onto the used market.

Shortly after this time, the Sultan lost interest in the nation’s airline. With lost interest came an end to abundant financial support from the government. Royal Omani had always been an entity more concerned with satisfying government fancies than generating profit. Thus, the airline struggled mightily with its finances. Its maintenance budget was slashed. No services were terminated but frequencies were cut, and aircraft condition suffered critically. International watchdogs rang the alarm as Royal Omani’s fleet appeared increasingly derelict. History would prove that they were not crying wolf.

In 1998, on a sweltering June day, Royal Omani’s second Embraer Brasilia, registered A4O-BB, departed Khasab Airport on a return hop from Muscat as SULTAN 341. This was the airframe’s fourth flight of the day. At 1123, the aircraft, which had been idling on the black asphalt for nearly half an hour waiting for a late passenger, began its take-off roll. For the proceeding week, crews had complained that the flight controls on A4O-BB were stiff and sometimes unresponsive. SULTAN 341 lifted off without incident, but problems arose when Pilot Gawas attempted to lessen the aircraft’s angle of ascent. Gawas’ input yielded no response. Gawas asked the first officer to assist in attempting to decrease the aircraft’s angle of attack. However, the controls remained unresponsive. Gawas began rocking the control column forwards and backwards trying to “unstick” it. His inputs became increasingly severe until he was successful in unsticking the elevator … into a steep dive. The Brasilia hurtled towards the ground and neither pilot nor co-pilot could unstick the elevators before it was too late. All 27 people on board perished in the impact and ensuing fire. Less than 120 seconds after take-off, disaster had struck.

The investigation into the SULTAN 341’s crash revealed that both flight crew and maintenance were to blame in the incident. The investigation quickly revealed that maintenance standards and practices at Royal Omani were woefully inadequate. The cause of the control surface stickiness which would most directly cause the crash was old hydraulic fluid. Hydraulic fluid pumps in the tail section of the Brasilia were clogged with detritus. Maintenance records do not document any attempt between 1989 and 1998 to change the hydraulic fluid or fluid filters in the aircraft. With this level of neglect, investigators noted it was only a matter of time before something went wrong. The extreme heat and aircraft’s delay on the ground had contributed to the accident by softening deposits of detritus in the hydraulic system which further contributed to the clogging. The investigators also acknowledged that the flight crew’s conduct contributed to the accident. Flight manuals did not explicitly cover a situation in which hydraulics were intermittently functional but under pressure the flight crew reacted in a rather manic, unorganised manner. Had they reacted more calmly perhaps the incident could have been avoided.

The report was released in 2000 and ushered in serious scrutiny by international regulators. Royal Omani was quickly banned from flying to many of its European destinations. The Sultan was displeased. The airline endured a management shakeup. However, no management shakeup could belay the fact that Royal Omani had a relatively old fleet of aircraft that were in appalling mechanical condition. The solution was another spending spree. In what would become the largest order in airline history, the carrier signed a deal to acquire an Airbus A340-500 and an A320-200 brand new.

The A320 arrived in 2001 and allowed for the retirement of the carrier’s DC-8 which was replaced in charter and supplementary operations by one of the carrier’s older A320-100s. In 2002, to much pomp and circumstance, Royal Omani’s new flagship touched down in Muscat. The A340-500 was chosen not for its statistical ability but rather because it was the newest aircraft in Airbus’s portfolio. Despite the fact that the 345 was designed to cover extremely long-distance routes, it actually debuted on the London route and also operated to Paris on occasion. The This was because the carrier’s L1011 was still allowed to fly to New York and the airline’s every changing host of Asian destinations but was banned by EU regulators concerned with the airline’s maintenance procedures. The 747SP was laid up in Muscat and remains parked on the edge of the airport to this day. In 2001, the airline also acquired a used Lansing Air System Brasilia to restore full regional services. It would eventually be registered as A4O-BC.

In 2011, the Tristar was becoming a maintenance nuisance. The airline successfully petitioned the Sultan for funds to procure an aircraft which could replace the aging Lockheed. To streamline the maintenance and thus decrease costs without, the carrier opted to search for another A340. Transnacional responded to the call with an A340-300 which had been retired a few years earlier. The aircraft, eventually registered A4O-KK, would feature a new livery. The livery updated and streamlined the stylized crown from the previous brand identity in addition to new titles. The new livery also featured a pattern on the tail which, while expensive to paint, was justified as substantially increasing the premium appearance of the brand. The Tristar remained in the fleet to be infrequently used as a supplement when the A340s required maintenance. The airline claimed that the fleet would be quickly repainted in the new livery. This did not occur.

In 2016, the A320neo finally hit the market and led to an influx and serious devaluation of A320ceos on the used market. Royal Omani pounced on the opportunity to acquire a recently retired Himmelbahn A320-200. This aircraft, while far from new, would supposedly decrease maintenance costs by allowing for the retirement of one of the A320-100s. The retired A320 would be retained for spare parts, which would eventually prove to be useful investment as the new newly acquired plane, registered as A4O-FB, would require a new emergency exit door in 2017 when it was hit by stray gunfire which pierced the an emergency exit window. It was in 2018 that the airline’s other A320-200, registered A4O-FC, received the new livery. Mechanics, supposedly of their own volition, chose to paint a mask reminiscent to those found on new A320neos on the aircraft while repainting it. Political opposition alleges that the paint feature was not an accident but rather a cheap attempt to make the airline appear more modern perpetrated by management hucksters.

The pandemic hit Royal Omani just as hard as many other carriers, but the Sultan pushed the airline to continue operations. The death of Oman’s Sultan was a national tragedy that struck the nation in the midst of Covid. It also left Royal Omani with an unsure future. Whilst the airline was nominally profitable before covid, without passengers, it lost money hand over fist. Thankfully, the new Sultan remained committed to the carrier. To show his commitment to continued interest in Royal Omani and celebrate relaxing pandemic border restrictions, he greenlit the acquisition of a used A340-300 from Australian carrier Nullarbor. The new aircraft would allow for the increasingly long maintenance stints the aging A340-500 required and a slight expansion of the airline’s long-distance network. This leaves the airline with current long-haul routes to New York JFK, London Heathrow, Hong Kong, Mumbai, and Bangkok Suvarnabhumi. The Sultan’s appetite for supporting the airline abated as economic conditions in Oman refused to improve. The agreement to purchase the A340 could not be voided, but further costs like repainting the aircraft could be curbed. Thus, the repainting process which would remove the aircraft’s previous Australian identity was cancelled partway through leaving A4O-KG in a half-finished state which was quickly, and rather sloppily, completed in key sections of the aircraft. It was only with the purchase of the 343 that the L1011 was officially retired.

Today, Royal Omani continues its steady march into the future. The fleet, particularly the A4O-CK which has been subjected to a few too many harsh sandstorms, shows signs of neglect. The airline’s financial situation is difficult to determine, but hardly seems steady. Notwithstanding, given the airline’s rocky past, it seems more likely than not that Royal Omani will continue to ply the skies for many years to come. The poster above depicts all aircraft actively registered in the Royal Omani fleet as they appeared in May 2022.

Following best practice, all brands associated with this post that do not belong to me - with the exception of the Sultan of Oman if you think that being the Sultan of a nation constitutes a brand - have been used with the consent of their respective owners or creators.

You nailed the Brazilian foreign debt part

You nailed the Brazilian foreign debt part

Livery and lore are 10/10. Love all the references to other brands from AE.

NICE FLEET

I love this... Especially the Transition livery on the a340! ![]()

love the aircraft's designs.

also, how long did it take to write the lore?

Thanks - it was written over a few days

You nailed the Brazilian foreign debt part

that was the intent. Enjoy the women and buy our planes

Livery and lore are 10/10. Love all the references to other brands from AE.

Happy to have been given the privilege of defacing a Nully craft!

NICE FLEET

Thank you!

I love this... Especially the Transition livery on the a340!

Thank you - I remain undecided whether I like that hybrid of the decrepit 345 more

Sign In

Sign In Create Account

Create Account

love the aircraft's designs.

also, how long did it take to write the lore?